Theme 2: Five Essential Reference Tools for a School Library Learning Commons

Five Essential Reference Tools for a School Library Learning Commons

(Mark Lynch, The Daily Toon)

(Mark Lynch, The Daily Toon)

In selecting five reference tools that I think would be essential for a school library learning commons, I first considered the widely used reference tools in a school library and followed the rule that “a good reference source is one that serves to answer a question” (Riedling and Houston 17). These reference materials include, but are not limited to, almanacs and yearbooks, bibliographies, atlases, dictionaries, encyclopedias, handbooks, indexes and abstracts, and style manuals.

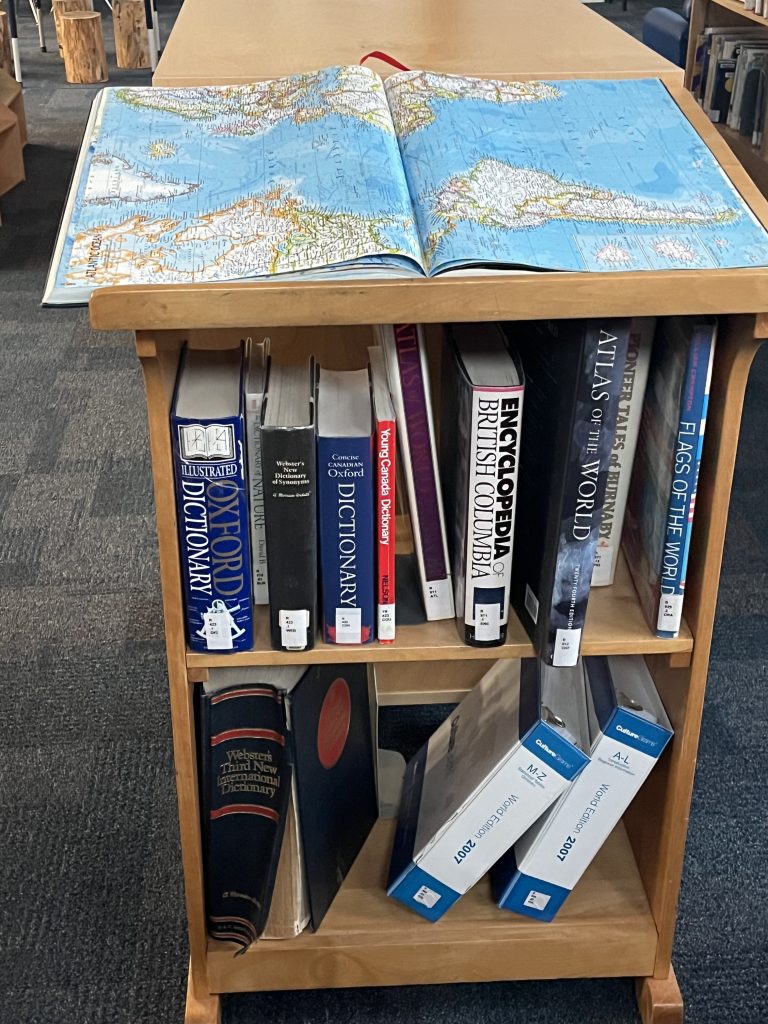

I visited our current school library reference section as it was important to consider what reference materials our students were currently and frequently using.

(Our school library reference section.)

(Our school library reference section.)

At first glance, our reference section seemed small but I had to remember that “it is better to have a small but relevant and up-to-date collection of materials than a large collection that is neither useful nor of good quality” (Riedling and Houston 25). I had a conversation with our current teacher-librarian who informed me that the two most frequently used resources from this reference section were the Young Canada Dictionary and the wide-open and inviting giant world Atlas. Knowing that “the school librarian collaborates with the teaching staff to develop an up-to-date collection of print an digital resources that appeal to differences in age, gender, ethnicity, reading abilities, and information needs” (AASL 2017) I also decided to speak with a few teachers (one primary teacher and two intermediate teachers) about what references they felt were most used and also most needed in a school library learning commons.

From these collegial conversations, it was derived that dictionaries and thesauri were what the teachers felt were most used or needed due to the high ELL student population at our school. The Young Canada Dictionary was mentioned by all three of the teachers, two of them who said they have class sets of this reference selection in their classrooms. The two intermediate teachers both expressed concerns with expanding their students’ writing skills inside of project-based learning and felt that a good quality thesaurus had a good part to play in this. (They said that they did have student thesauruses in their classrooms, but it was noticeably missing from the library reference section when they were doing schoolwork in the library.) All three teachers were in agreement that what they noticed the children personally gravitating to most were the Guinness Book of World Records (not pictured above as they are shelved in a different location). This by far was the most popular choice for students hoping to discover exciting factual information. Lastly, the primary staff member said that she often saw her students perusing and flipping through pages of the large world atlas. She felt that at their age, their interest wasn’t necessarily driven by a search for specific geographical information but rather by a curiosity to explore, especially since the giant book was open and on clear display, inviting them in. Regardless of the motivation, she noted that the students’ faces shone with discovery and awe when using this gigantic resource. They became aware for the first time of where places were in the world and their relation/proximity to each other and the atlas was a huge hit with her class during their weekly library time.

It was extremely useful for me have these conversations with the teacher-librarian and a few colleagues because one should always bear in mind to “evaluate the materials in [the] collection on a regular basis to determine if the collection meets the needs of the students, teachers, and community” (Riedling and Houston 20) as well as be conscious that “the collection [should] evolve[s] as the needs of the community evolve” (Riedling and Houston 19). I think that decisions for reference materials should always be built on cooperative an collaborative conversations in order to better understand the needs and habits of the teachers, students and school community.

I now had an idea that a dictionary, a thesaurus, an atlas, and the Guiness Book of World records were four resources that I could anticipate would have frequency of use. However, my mind kept returning to a resource being one could ‘answer a specific question.’ As a fairly experienced teacher, I knew the variety and scope of questions that students can have based on not only their curricular studies and educational needs, but also simply from their own curiosities. I knew that an encyclopedia would offer a comprehensive collection of information on a wide variety of topics, covering a large scope, which would be very advantageous for addressing these questions. Typically designed to be reliable sources of information, I felt that this would be the necessary fifth resource.

Now came the task of deciding which reputable companies these resources would come from and to check their reading level to make sure they would be appropriate and usable for elementary age students. I also needed to determine whether or not theses 5 references would be best purchased in print form or digital form. This would mean:

- Evaluating the resource based on sound criteria.

- Considering the cost of the resource.

- Anticipating the frequency and length of use. (Riedling and Houston 23)

I also thought it would be important to keep in mind what the BC Ministry of Education outlines in general for any learning resources used in the school system. The ministry outlines that resources should:

(ERAC 5)

(ERAC 5)

More particularly for reference resources, the criteria as outlined in chapter two of Riedling and Houston’s Reference Skills for the School Librarian assisted me in evaluating reference resources to meet the students’ informational needs. This meant to consider:

1. Scope

2. Accuracy, Authority, and bias

3. Arrangement and Presentation

4. Relation to Similar Works

5. Timeliness and Permanence

6. Accessibility/Diversity

7. Cost

I knew that “by using appropriate evaluation tools and criteria, the school librarian is better able to judge whether a particular source meets the needs of the student population” (Riedling and Houston 23). These kinds of appropriate evaluation tools could include a reference evaluation rubric such as this one here, the very detailed ERAC resource evaluation checklist here, and also viewing a number of reviews through these suggested sites below:

All Grade Levels:

- American Libraries (American Library Association) American Libraries magazine, available in both print and online format, lists outstanding reference sources for small and medium-sized libraries.

- The Reference and User Services Association’s (RUSA) Reference Sources Committee lists the best reference materials of the year online. americanlibrariesmagazine.org/www.ala.org/

- American Reference books Annual (Libraries Unlimited, Inc.) American Reference books Annual (ARBA) has been published annually since 1970 and is currently available in print and online format, including annotations, reviews, and other commentary useful for selection and evaluation of reference materials for school librarians. The online version offers a thirty- day trial subscription.www.arbaonline.com/

- Booklist (American Library Association) booklist magazine is published semimonthly by the American Library Association and includes Reference Books Bulletin, which focuses specifically on reference resources for the school library. The magazine reviews current books, videos, and software and provides monthly author/title indexes as well as semiannual cumulative indexes. booklist online provides continuous access to these resources. The online version offers a free trial subscription. www.booklistonline.com/

- The Horn book Magazine (The Horn Book, Inc.) The Horn book Magazine is published bimonthly with a focus on children’s resources, including reference materials. The magazine also publishes reviews, articles, editorials, and columns related to children’s literature. The Horn book Guide is published annually and contains reviews of hardback and paperback books, including bibliographic information, size, age level, summary of content, and other pertinent information regarding the selection of elementary materials. The Horn book Guide is also available online. www.hbook.com

- Internet@Schools (Information Today, Inc.) Internet@Schools is available in print and online formats and provides reviews of books, databases and online sources, hardware, and other technologies appropriate for K–12 school libraries. www.internetatschools.com/

- School Library Journal (MediaSource Inc.) School Library Journal (SLJ) is a leading magazine for school librarians. One half of SLJ is dedicated to critical reviews of print and electronic resources. SLJ provides twelve issues per year; the December copy presents the editor’s choices for Best Books of the Year. The SLJ companion Web site provides an archive of past issues plus reviews, newsletters, and blogs, some of which do not require a subscription. www.schoollibraryjournal.com

Particularly Primary:

- Children’s Core Collection (H. W. Wilson/EBSCO) The Children’s Core Collection online database provides a wide-ranging annotated listing of more than 13,000 of the best fiction and nonfiction books, new and established, written for children from preschool through sixth grade. A free trial subscription is available. www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/childrens-core-collection

Websites:

- KidsClick.com(www.KidsClick.com) KidsClick provides educational and fun software just for kids!

- InternetPublicLibrary(http://www.ipl.org) The IPL is maintained by a consortium of university library science programs and serves as a portal for authoritative Web resources for children and adults. There are separate sections for children and adults, online periodicals, and an alphabetical subject guide. The Reference area in the Kidspace section includes links such as Homework Help, Dictionaries, Encyclopedias, and more.

(Riedling and Houston 20-22)

There are many helpful aids for suitable selection and evaluation of reference materials. Using a combination of these helped in determining whether materials would be appropriate for inclusion.

I also stand firm that a mix of print and digital formats should be maintained in the reference section, considering the numerous advantages and disadvantages of each. For example, print references offer less screen time, fewer visual distractions on the page, and no yearly fees. However, they can quickly become outdated and worn/dog-eared. On the other hand, digital references can be quick to use, consume less space, and offer automatic updates, but access to sufficient digital equipment is problem as well as navigating complex interfaces and having costly subscriptions. I was pleased to see that our school currently has both print and digital references that are used by our students, and I wanted to maintain this variety as well.

In conclusion, after processing all of the information above, the 5 resources that I think would be essential additions to the reference section of a school library learning commons are:

- Young Canada Dictionary – print form, clear simplistic format, short explanations in language easy to understand. Aimed at all elementary grades, supports all areas of the curriculum. Medium scope of 6500+ words (however words are chosen match the level of learners).Illustrations to support ELL learners. Low cost: $26.86. Highly reputable educational publishing company for over a century.

- The American Heritage Children’s Thesaurus – print form, lack of school computers makes hard copy a quicker search. Simple language aimed for grades 3-7. Medium scope of 4000 + entries with 36,000+ synonyms. Supports all areas of the curriculum, particularly written work. Unconvaluted format with illustrations included to support ELL learners. Low cost: $27.99. Reputable publishing company since 1949. Booklist reviewed and recommended.

- World Book Kids – digital form encyclopedia, supports vast topic areas of inquiry, pertains to all areas of curriculum. Predictive search engine to aid young learners who are vocabulary building (ELL) and also exploration through image-based navigation is possible. Extra hands-on activities and games to solidify learning, promotes digital literacy at the same time as information literacy. Annual cost: $99.00. Extremely reputable publishing company since 1917.

- Guinness Book of World Records – print form, one of the most signed out resources from our school library. Attractive layout, vibrant colours, variety of fonts and illustrations appealing to kids. Exposure to key features of information display (charts, graphs, labels, fact boxes etc.) Curricular connections to all subject areas. Includes both classic and new records. Language is suitable for elementary students. New hybrid feature is hours of videos via QR codes placed throughout the book. Low cost, high frequency of use: $24.22. Reputable publisher since 1955.

- National Geographic Atlas of the World – print form, large size maps of every region of the world, as well as accompanying graphics showing important population, environmental, and economic patterns. Comprehensive index cross-referencing more than 150,000 place names. Highly visual reference, excellent for visual learners. Pertains to social studies, history, science, math and languages or cultural curriculum. High cost: $264.52. Extremely reputable publishing company since 1888.

This last choice for the National Geographic Atlas of the World was a difficult one for me due to the price, especially when we know that digital resources such as Atlapedia or Google Earth can be accessed for free. However, the reason I opted to go with a print format for this particular item was due to the colossal size of this reference item and the fact that from collegial conversation, this was what was said to have attracted students to its use. Digital formats would certainly provide a much more interactive ability to zoom in to locations, have ‘real’ satellite views, links to information about the area and more. However, there was something about the sheer grandeur of this reference resource (not to mention the mapping skills that it would help instil when searching from page to page) that I simply could not pass up on. Although there is high cost associated with this print form, the longevity and steadfastness of it’s content means that it will not need to be replaced as quickly as other reference items may as “age need not be a primary criterion when weeding geographical materials” (Riedling and Houston 76). Lastly, the teacher-librarian could also provide access to a digital altas reference in tandem.

In closing, I think the most important part of having these essential reference resource tools in the school library learning commons is actually the teacher-librarian him or her self, and the information skill instruction that accompanies using these resources. There is a positive relationship between the quality of reference sources and “between the quality of information services provided in the library and student learning” (Riedling and Houston 6). We have to remember that kids aren’t born with these skills innately and that our job is to help create information literate citizens capable of using a variety of information reference materials. The video below is a fun reminder of the need for this instruction.

Works Cited

AASL (American Association of School Librarians). Empowering Learners: Guidelines for School Library Media Programs. AASL, 2017.

Educational Resource Acquisition Consortium (ERAC). Evaluating, Selecting and Acquiring Learning Resources: A Guide. 2008. bctla.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/erac_wb.pdf. Accessed 25 Feb. 2024

REACT. “Teens React to Encyclopedias” YouTube, uploaded by REACT, 12 July 2015, https:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=X7aJ3xaDMuM. Accessed 25 Feb. 2024.

Riedling, A. M., & Houston, C. Reference Skills for the School Librarian:Tools and Tips. 4th ed., Libraries Unlimited, 2019.