Assignment 3: Improving Reference Services in a School Library Learning Commons

Reference services in a Library Learning Commons include reference interview processes, library policies and of course the carefully selected reference materials themselves. Healthy reference services are imperative to any library learning commons because they encompass the “activities required to meet the information needs of the library’s clientele” (Reitz).

Reference Collection

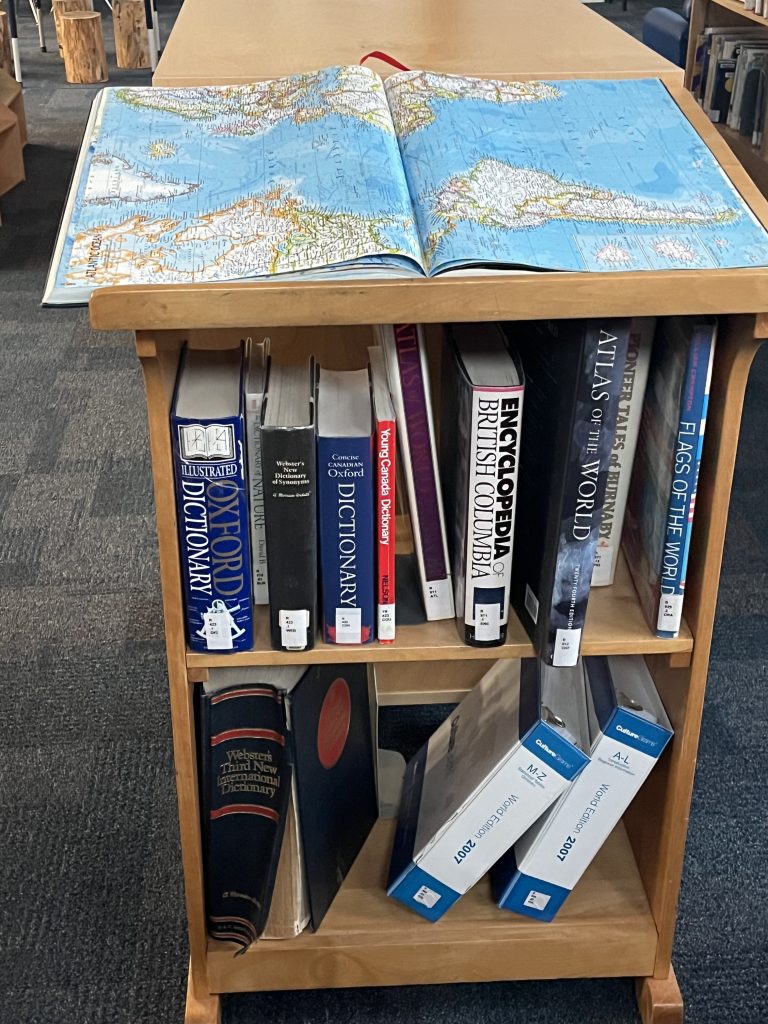

When attempting to improve any section of the school library learning commons it is essential to first analyze and evaluate what is already there. At first glance, our school library reference section is quite small, as pictured below.

(Our school library reference section.)

(Our school library reference section.)

Remembering that “it is better to have a small but relevant and up-to-date collection of materials than a large collection that is neither useful nor of good quality” (Riedling and Houston 25) it was important not to ‘judge a book by it’s cover’ and instead investigate all that our reference section had to offer including any digital reference resources available to library patrons. While examining this section more closely, it was made known to me by our current teacher-librarian that there were some other student friendly reference sources located on a few of the library shelves as well. This made for a more robust reference collection than initially seen here, and I was happy to know that there were more reference materials available to students and staff than I had expected. Below is a complete list of the Parkcrest School Library Reference Resources available:

Parkcrest School Library Reference Resources

The reference collection print resources have an average age of 1995. Although this seems quite shocking, in a small selection of 34 resources it only takes a few such as the 1973 Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary of Synonyms and 1976 Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary to significantly lower the average age of the reference collection. I presumed that these items hadn’t been updated due to their significant cost, but then I realized that both the Merriam-Webster Dictionary and Merriam-Webster Thesaurus had been provided as digital resources now. “Dictionary revision is never ending; a major advantage of electronic dictionaries is rapid update” (Riedling and Houston 58). The teacher-librarian explained that these older print versions were left in the resource section for quick searches as sometimes the time it takes to boost the computers up, open the website, navigate and search is longer than flipping through a print reference. Secondly our learning commons only has three computer stations which are often in use with students searching the library catalogue and performing other research. With this rationale for these print references to remain, and our budget running tight, I think I would still like to see them updated and try to do a cost effective update. The selecting, I would need to consider Riedling and Houstons’ criteria of authority, format, currency and accuracy below:

I would stick with the reputable publisher, Merriam-Webster, look for precise, accurate definitions in a format user friendly for elementary school students and of a current publication date. Therefore, I would choose the Merriam-Webster Elementary Dictionary published in 2023 for $32.80 through Amazon. It’s large hardcover format, clear and concise definitions and inclusion of some illustrations makes this a more current and inviting print dictionary reference for elementary students. This updated version would be housed on the shelves with the other student friendly dictionaries and would replace A Basic Dictionary: a Student’s Reference which is looking really worn and tattered and was published in 1994. For the reference section itself, I would consider purchasing a Merriam-Webster pocket-sized printed set of dictionary, thesaurus and vocabulary builder (pictured below) as it is $28.69 for all three and would provide updated, current print resources for staff and upper intermediate students. Although the format of this trio is not ideal (small size and paperback) this could serve as a cost effective replacement of these two dated selections until there is more room in our school budget for full unabridged, updated large hardcover editions (approx. $200+ each). With these improvements, there would be current, updated print versions on the shelves for students and teachers and the pocket-sized trio could be given to a classroom once the large hardback versions are acquired.

After studying the collection map of the reference sections of the library, other improvements that I would like to see made are:

- For the student reference section on the shelves, a few more English-Chinese dictionaries would be beneficial due to the high volume of Chinese speaking ELL students in our school. The Renyi Picture Dictionary we currently have on our shelves is in Cantonese and a lot of our students are Mandarin speaking. Considering that “vocabulary building and language usage are cornerstones of literacy and learning” (Beaudry) I feel it is important to support our students by providing English-Mandarin language support. Therefore I would take a look at potential resources for this using the following selection criteria developed by William A. Katz:

- Scope/Emphasis: The general coverage, identifies the range of topics

- Reading Entries look up a subject you know to assess scope/emphasis

- Authority: the names and credentials of the people responsible

- Style: writing style for intended audience, language level

- Recency: continuous revision, copyright date

- Viewpoint/ Objectivity: keep in mind intended audience, topics included

- Arrangement and Entry

- Index

- Format: illustrations, font type/size, binding and size

- Cost

I would choose the Mandarin Chinese English Bilingual Visual Dictionary published by the reputable DK publishing company and The New Oxford Picture Dictionary: English-Chinese published by Oxford University Press. Both are large visual dictionaries presented in a format that is appealing to elementary aged children with vibrant illustrations, clearly organized headings and simple explanations throughout. Each text covers wide scope of common English vocabulary and the cost for each resource is a reasonable $26.64 and $26.29 respectively.

2. For our digital resources, access to a digital atlas may be valuable. Although historical geographical questions can be located in older atlases and geographical resources as “age need not be a primary criterion when weeding geographical materials” (Riedling and Houston 76), responding to geographical questions with a need for current information may require the use of online resources. “With the wealth of geographical sources currently online, it is now significantly less complicated to fulfill the diverse requests required by students” (Riedling and Houston 76). Therefore, I would once again use Reidling and Houston’s selection and evaluation criteria, this time for geographic resources, to provide an easily accessible link to a quality, cost-effective (free), online atlas that has suitable format and navigation for the intended elementary audience, such as Atlapeida ((Latimer Clarke Co.).

With improvements now made to the reference section, the shelved reference section and the digital reference resource section of the collection map I took the time to filter through the resources individually to see if I could catch any further improvements to be made. I also checked in with some teaching staff as to their thoughts on the reference collection which provided really valuable insight. “Continuous collaboration with teachers and eliciting the expert advice of the school’s faculty members and drawing on their experience and knowledge” (Reidling and Houston 26) is crucial to continuous improvement in developing an effective reference collection.

When filtering through I noticed that Pioneer Tales of Burnaby was very fact based account of settlers in Burnaby but didn’t account for the indigenous perspective. Published in 1987, this extensive resource presents a very historical, fact-based account and timeline of the development of the city on which this school library is located. Early Burnaby is recalled by the settlers themselves who arrived from every corner of the world between 1888 and 1930. As much as I do think it is a valuable resource historically in order to understand the architecture, infrastructure, trading and business, and multicultural community of Burnaby, I feel strongly that it is essential to be paired with text of the First Peoples account of early settlement times including the truth, destruction and displacement of the Coast Salish indigenous peoples on whose traditional territory this city stands. Therefore, my approach to this would be to contact the Burnaby District Indigenous Resource Teacher and the District Principal of Indigenous Education who would have much more knowledge on authentic resources to shelve alongside this one. Pioneer Tales of Burnaby is historical non-fiction and chronicles the development of this city factually, and I don’t believe it should be pulled or censored from the shelves. However one has to consider critical omissions in a reference resource and not just the validity of what is presented. The Burnaby Village Museum is a good example of a a repository of knowledge that presents the historical narrative of the history of Burnaby, including the dispossession of the land and resources forcibly from Indigenous people, through it’s History Learning Guide found here. The solution may be to receive a printed copy of the Indigenous History in burnaby Resource Guide (link here, and endorsed by the Burnaby Board of Education) to shelve together with the Pioneer Tales of Burnaby. Education from the teacher-librarian would be necessary for anyone signing out these resources in order encourage borrowing the two in tandem. I do not have the knowledge of authentic resources of the indigenous peoples during early Burnaby settlement and therefore I recognize the need for specialist input in this selection.

In speaking with teaching staff I learned that the Dictionary of Nature although one of the oldest in the reference section was one with the most currently used and circulated due to outdoor education in the primary grades. I also considered the digital resource Canada Info. Canada Info. by Craig Marlatt hard to evaluate for accuracy due too it’s single one-man authorship and little reviews. I knew could use the strategy of going to topics that I know a lot about factually and validate some accuracy this way, plus compare information to other reputable sites, but even though I didn’t find anything inaccurate in doing this I still wondered if this resource was worth the risk. Especially when The Canadian Encyclopedia by the extremely reputable Historical Canada was also readily available to students digitally. This was when teacher input sprang forth about the user-ease of Canada Info.and it’s kid-friendly navigability. Both the teachers and their students loved using this simple site. I was reminded in these instances that “selection is not completely the responsibility of the school librarian. This process also belongs to administrators, teachers, students, parents, and community members. Input from these people is essential for a useful and appropriate reference collection” (Riedling and Houston 20).

One last comment to be made regarding the reference resources available in the Parkcrest school library is that there were in fact numerous biographies scattered throughout the non-fiction shelves of the collection. These resources were located in the subject or themed areas to which they belonged. For example, a biography of Mario Lemieux was in the sports section alongside hockey related text and a biography of Chris Hadfield in the space section. This made sense to me and I understood the rationale of location paired with topics of specific interest. However, I might consider doing some kind of display and book talk to showcase and spotlight biographies in order to highlight and generate interest in this genre of text.

Reference Services

Improving reference services in a school library goes beyond providing access to exemplary reference materials. “Today, students certainly have access to more information, but this does not necessarily mean that they have more knowledge. Is anyone the wiser because of the availability of limitless information?” (Riedling and Houston 101). It is the teacher-librarian’s responsibility to assist in creating information literate citizens who are able to “effectively navigate the sea of information to obtain desired answers from authoritative sources” (Riedling and Houston 101). This is deemed essential by the Canadian Library Association and is one of the five core standards of practice in their document Leading Learning. “The teacher-librarian leads the school community in the design of information literacy learning strategies and processes in order to empower independent learners” (CLA 17).

Helping create information literate citizens can start with the reference interview. “Almost every reference request from a student or teacher may provide an informal or formal opportunity to teach information literacy skills” (Beaudry). Durning the reference interview a conversation occurs between a librarian and a library user where the librarian first seeks to clarify the user’s information requirements and then guides them to relevant information resources.“In the reference interview, the school librarian’s goals are to determine efficiently and productively the nature, quantity, and level of information the student requires, as well as the most appropriate format” (Riedling and Houston 89). In my reference interviews I would first be prepared to distinguish whether the questions was, as Riedling and Houston define, a reader’s advisory question (recommending good leisure reading) or as Katz defines, a direct question (where something is in the library), a ready reference question, (answered with short, straightforward and factual answer), a specific search question (involving specific reference material leading the patron to more information) or a research question (involves trail and error browsing). Determining the users needs by asking further clarifying questions will not only help direct the the pathway to information but just as importantly will open the lines of communication and create a warm and approachable feeling of support. I would follow the five important elements, or stages, of the reference interview.

- Approachability: Going from initial contact with the student to actually find out their needs.

- Listening: A good listener gives students a chance to tell you what they want.

- Interviewing: Discover what the student really wants.

- Searching: Keep the student informed of progress.

- Answering: Speak clearly and distinctly. (Riedling and Houston 90)

This will create a feeling of trust and genuine care towards the patron from the librarian, who following the reference interview must continue the reference process of assisting the user in understanding and navigating the information resources effectively.

For teachers especially, this type of focused listening and interest on the part of the librarian can open the door for collaboration where personal concerns are legitimate and growth and change in teaching practices can occur. Using the Concerns Based Adoption Model below, I would be able to “implement a developmentally appropriate support sequence and let peoples’ readiness and stage of concern drive when the program or mentoring shifts its focus, not a calendar or the plan” (CBAM 11).

The current reference services and processes in our school library involve concerned and caring reference interviews and direction on part of the teacher-librarian to assist in helping create information literate citizens through proper use of reference materials. What I would like to improve, or see more of, is a collaborative approach to teaching curriculum with staff and students that considers an inquiry-based approach to learning where research is open ended and the end result is not necessarily the goal but the competency skills learned along the way are. Our library schedule is mostly focused on book exchange and some research support but not larger collaborative ventures where the teacher and the librarian work together to collaborate on curriculum instruction including assessment and evaluation of the collaborative processes. This is no critique to the current teacher-librarian as she is given 0.5 FTE time for a school of approx. 300 students and 13 divisions. Understaffing and underfunding of school libraries is a common problem in the public system. Creative ways to include this collaborative time might be in motivating staff and students into creating collaborative lunchtime clubs such as Makerpaces Mondays or an ADST Club. This would provide opportunities for teacher collaboration and also building information literate citizens through questions that arise when problem-solving. These hands-on kinds of activities are not only inviting and engaging for students but also promote development of the core competencies of creative and critical thinking, This kind of collaborative work is what excites me about becoming a teacher-librarian. “As long as students require information and guidance in becoming effective users of information and ideas, there will be a need for school librarians and school libraries” (Riedling and Houston 107).

Some practical improvements to current reference services in our school library that came to mind were the need for more access to the library catalog (computers) during library blocks. Students have been trained to be quite independent in their search for reading materials and also in their use of some of the digital resources our library offers. However, there are currently only three accessible computers in our school library. The newly built structure allows for eight across it’s “digital bar” (complete with barstools) and I would like to see more technology made available here for students. The procedures for this would involve meeting with the tech.committee, the finance committee and administration to advocate for funding for this. Rationales would include creating both information literate and digital literate students. This pertains directly to the district’s recent Education Technology Plan that was implemented in November of 2023 and includes the objectives below:

(Image from Burnaby School District 41, Education Technology Plan)

(Image from Burnaby School District 41, Education Technology Plan)

Another improvement that I think will be necessary during my initial years as a teacher-librarian relates to reader advisory questions. One way that I noticed an amazing former teacher-librarian use to engage reluctant readers was that she would steer the conversation away from reading and ask the child “If you don’t like to read what do you like to do?”. Most students would easily exclaim other interests they liked such as collecting frogs, or going camping, or playing video games. Next thing you know, she’d walk right over and pull some non-fiction books about frogs, a mystery book about camping in the dark and a graphic novel about a boy caught inside of a video game. This teacher librarian read so much children’s and young adult literature during her spare time that honestly…she’d be able to find a book about a frog who went camping and missed his video games. It was unreal. I’ve never forgotten it. A child would seemingly say two totally unrelated things, “I like ballet and pigs” and this teacher-librarian would exclaim, “Well then Ballerina Pig by Pippa Goodhart is the one for you!”. Obviously this came with years of experience, but I think that one way that we can support students who are hesitant to take books out’ is to read a LOT ourselves, to know our collections well and to be curious about their other interests. Since I am brand new to teacher-librarianship and I clearly haven’t read all of the youth titles in our school library, I think a reference tool that would improve our library learning commons (or at least improve a new teacher-librarian in it) would be a subscription to Novelist. Novelist K-8 is a great reference tool to help find just the right book for young readers. Novelist considers subject, genre and appeal and was created for librarians by librarians. This is a place for good recommendations. Unfortunately, the website doesn’t show pricing at all and so therefore cost may be a hindrance. This is when ‘human references’ (other teacher-librarians in your district) are of vital importance. Being involved in regular teacher-librarian meetings and chat groups would be crucial to my reference services. Learning and being mentored, not only in teacher-librarian duties but also in book recommendations for students, by experienced teacher-librarians would be extremely beneficial, Burnaby has a very strong teacher-librarian cohort with monthly meetings and connections through chat groups and also mentorship programs. You can always be assured to have an experienced teacher-librarian on speed dial.

Reference Policies and Procedures

These suggested ways of improving the reference materials and reference services in the school library should come with clear policies and procedures in place. Although our school does not have it’s own specific weeding or selection policies, the district has placed some general guidelines for the selection of learning resources here. I think it would be advantageous to write a writing a weeding and selection policy for reference resources, including input and collaboration from administration and interested staff. The teacher-librarian would be responsible for creating the outline of procedures, but staff and administration should include input what they deem important to consider as well (eg. when and how, should materials be run by staff prior to weeding, processes for new purchases after requests are made). Even though the autonomy for the decision of what reference resources are necessary to be weeded and what reference resources are an excellent new selection should lie on the trained professionalism of the teacher-librarian, I believe that a collaborative approach to final decision-making is always best. This involves transparency to the staff and is also an opportunity to explain intent behind the changes and reassure any further plans and pursuits (often when budget allows). Finance committee meetings, professional development committee meetings and staff meetings are all opportune times to communicate policies and procedures for improving reference resources with staff.

As for the evaluation of quality reference services. Successful reference services should ultimately create a rise in information literate students and staff who are able to find information and use a variety of reference resources more independently. However, follow up to determine the success of programming and teaching could come in the form of informal interviews, surveys and verbal feedback in staff meetings. Riedling and Houston state that “building a library collection is an ongoing activity. The collection evolves as the needs of the community evolve” (Riedling and Houston 19). I believe this to also be true about all reference services and processes offered in the library. Ongoing communication with staff and administration regarding the use of reference services and their effectiveness will provide valuable feedback for further improvements and necessary change.

Improving reference services in a school library learning commons is an ongoing process. Guided by policies and procedures, facilitated by trained teacher-librarians and supported by collaborative staff and administration, a school library’s reference services can having a lasting impact on helping develop information literate citizens.

“Excellence in school library programs requires teacher-librarians to be leaders in the school community. They see the big picture in curriculum implementation, particularly in developing students’ information literacy and lifelong reading and learning habits. They keep abreast of new developments in curriculum, instruction and technology, and they assist other teachers with implementing these developments in their classroom programs. They are active in professional organizations and on advisory and decision-making bodies at the school, district, provincial and national level. They share recent research findings and facilitate research programs within the school and provide professional development at a variety of levels” (Asselin 57).

Throughout the teacher-librarianship program, understanding the multi-faceted role that teacher-librarians have in the library learning commons has been profoundly revealing. As Riedling and Houston conclude, “school libraries and reference services are intended to enrich society and contribute to students’ efforts to learn. The challenge is ours” (Riedling and Houston 14).

Works Cited

Asselin, M., Branch, J.,and Oberg, D. Achieving Information Literacy: Standards for School Library Programs in Canada. Canadian Association for School Libraries, 2006.

Beaudry, R. LIBE 467 Information Service I. https://canvas.ubc.ca/courses/131637/pages/ Accessed 5 April 2024.

Canadian Library Association (CLA). Leading Learning: Standards of Practice for School Library Learning Commons in Canada, 2014. llsop.canadianschoollibraries.ca/wpcontent/uploads/2016/09/llsop.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2024.

Loucks-Horsley, S. The Concerns-Based Adoption Model: A Model for Change in Individuals. 1996, https://s3.wp.wsu.edu/ uploads/sites/731/2015/07/CBAM-explanation.pdf. Accessed 5 April 2024.

Reitz, J. Online Dictionary for Library and Information Science (ODLIS). https://odlis.abc- clio.com/odlis_r.html. Accessed 5 April 2024.

Riedling, A. M., & Houston, C. Reference Skills for the School Librarian:Tools and Tips. 4th ed., Libraries Unlimited, 2019.