Another of our guides this year will be the Goddess of All Things, AKA singer/songwriter/painter superstar Canadian Joni Mitchell. Your indoctrination into worship gentle guidance towards an appreciation of her talents begins here.

One of the many many many (many) ways in which Joni Mitchell changed the frequency of music and culture is her use of what are called “open tunings” for her guitar.

Standard tuning for the strings on a six-string guitar works like this: “EADGBE—three intervals of a fourth (low E to A, A to D and D to G), followed by a major third (G to B), followed by one more fourth (B to the high E)” [I’ve never played a guitar in my life and have only a vague sense of what that last quote means – but enough to get a rough idea of it and so move on, so thank you, Jeff Owens on fender.com].

Joni Mitchell threw that idea out the window and created a whole new soundscape of alternative tunings. Take a slow read of this (from “The Guitar Tuning Odyssey of Joni Mitchell,” by Jeffrey Pepper Rogers) (how’s that for a name?) and consider how what she has to say might serve as a metaphor for your life in class and your life in general:

So how does Mitchell discover the tunings and fingerings that create these expansive harmonies? Here’s how she described the process: “You’re twiddling and you find the tuning. Now the left hand has to learn where the chords are, because it’s a whole new ballpark, right? So you’re groping around, looking for where the chords are, using very simple shapes. Put it in a tuning and you’ve got four chords immediately—open, barre five, barre seven, and your higher octave, like half fingering on the 12th. Then you’ve got to find where the interesting colors are—that’s the exciting part.

“Sometimes I’ll tune to some piece of music and find [an open tuning] that way, sometimes I just find one going from one to another, and sometimes I’ll tune to the environment. Like ‘The Magdalene Laundries’ [from Turbulent Indigo; the tuning is B F# B E A E]: I tuned to the day in a certain place, taking the pitch of birdsongs and the general frequency sitting on a rock in that landscape.”

Mitchell likens her use of continually changing tunings to sitting down at a typewriter on which the letters are rearranged each day. It’s inevitable that you get lost and type some gibberish, and those mistakes are actually the main reason to use this system in the first place. “If you’re only working off what you know, then you can’t grow,” she said. “It’s only through error that discovery is made, and in order to discover you have to set up some sort of situation with a random element—a strange attractor, using contemporary physics terms. The more I can surprise myself, the more I’ll stay in this business, and the twiddling of the notes is one way to keep the pilgrimage going. You’re constantly pulling the rug out from under yourself, so you don’t get a chance to settle into any kind of formula.”

Joni Mitchell’s use of open tuning arose partially as compensation for a childhood bout of polio, which left the left side of her body (including her left hand, which forms the chords on a guitar) weakened, and partially, it seems to me, as a result of an innate deep restlessness and a natural tendency to question standards and norms and move toward the new.

In 2015, Joni Mitchell suffered a brain aneurysm that took away her ability to speak and walk. She had to teach her brain how to do these things again. And then she did something not even her doctors expected her to be able to do: she relearned how to play the guitar (by watching old videos of herself to see where her fingers went). Her doctors attributed her ability to do this to her natural will and grit, which are two words that it might be a good idea for us to investigate this year and find where they live within each of us.

On July 24, Joni made a surprise appearance at the Newport Folk Music Festival, and, among other wonders and delights, treated the audience to a guitar solo, the first time she had played guitar in front of an audience in 8660 days.

What are you willing to learn how to do over again this year? What are you will to risk “failing” at, being an infant again with, like Joni had to do with her guitar, in order to put it back together again in a new, different, deeper, more complex way?

Are you willing to evolve?

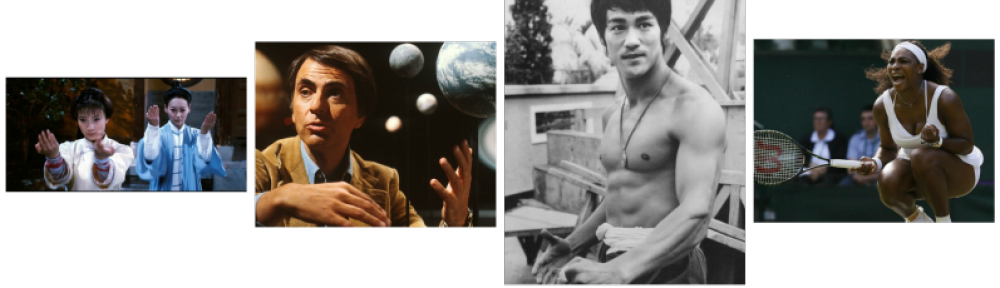

Hopefully you are beginning to get a sense of why Joni Mitchell, along with Bob Dylan, is widely considered the most influential singer-songwriter of all time (and she really considers herself to be a painter, first and foremost, and we haven’t even touched on that yet!). My secret plan hope is that by the end of this year you will understand why this is so, and that whenever anyone anywhere says the words “Joni Mitchell,” you will stop whenever it is that you are doing and reflexively do this: